Dr. Brad Muller

The source of much of this material is the COMET® Website at https://meted.ucar.edu/ of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR) pursuant to a Cooperative Agreements with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. ©1997-2007 University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. All Rights Reserved.

Mountain waves are standing atmospheric

waves caused by airflow over mountains, analogous to standing

waves in water from flow over a boulder:

Time lapse animation of lenticular clouds in a standing wave over Las Vegas.

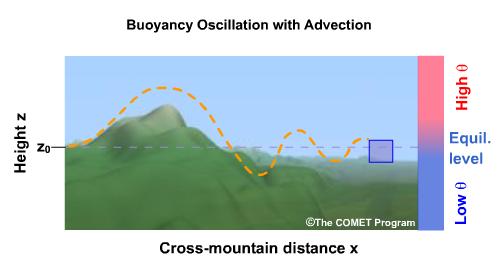

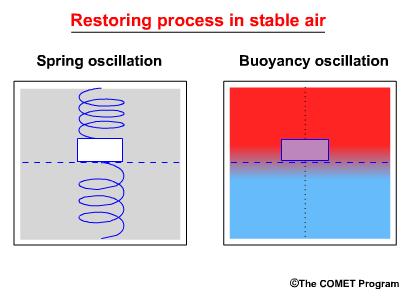

They are caused by "bouyancy oscillations" in the atmosphere.

Time lapse animation of lenticular clouds in a standing wave over Las Vegas.

They are caused by "bouyancy oscillations" in the atmosphere.

Mountain waves occur when there is a stable layer near or just above mountain top height, and the air flow is more or less perpendicular to the mountains.

Types of Mountain Waves

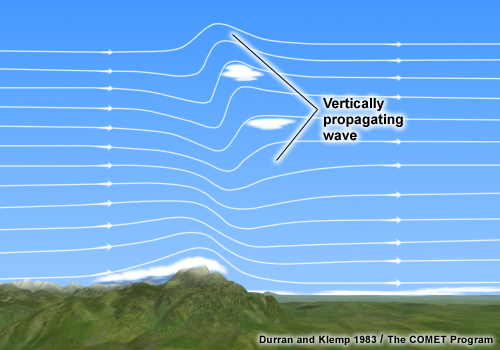

There are two main types of mountain waves: trapped waves and vertically propagating waves.

Trapped Waves

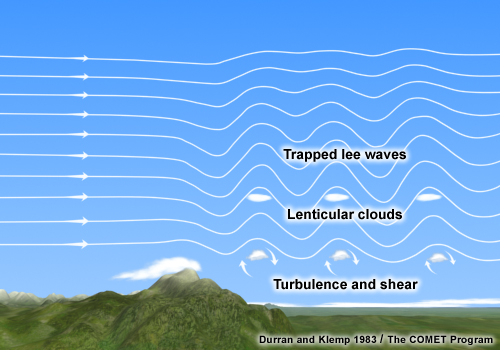

Trapped waves occur when wind speed above the mountain increases sharply with height and when stability decreases above the mountain top stable layer.

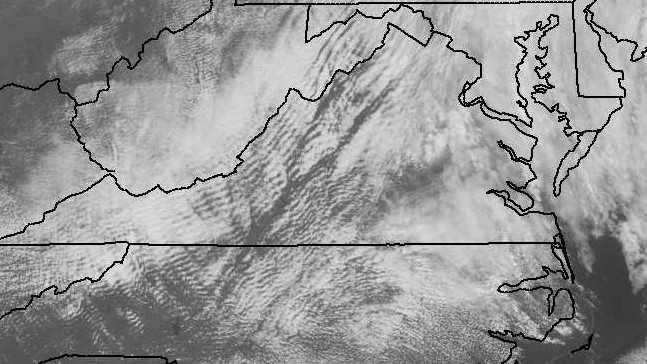

VIS image, trapped waves:

Airflow over mountains:

Mountain waves are not always turbulent, but they can be. The horizontal spacing of the waves is related to the wind speed over the mountains. Higher speeds yield longer wavelengths (greater spacing). Faster wind speeds also are related to stronger mountain wave turbulence.

Vertically Propagating Waves

Vertically

propagating waves occur when

-Wind speed above the mountain does not increase significantly.

-Stability increases above the mountain top stable layer.

-Wind speed above the mountain does not increase significantly.

-Stability increases above the mountain top stable layer.

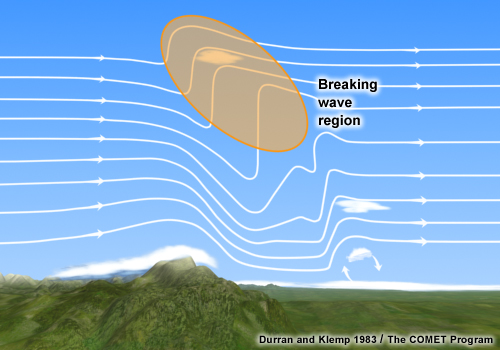

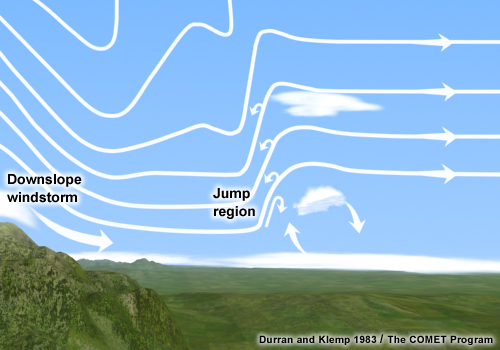

Vertically propagating waves can become very turbulent in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere in the so-called "breaking wave" region, and also in the "hydraulic jump" region of the wave. They are closely related to downslope wind storms such as Chinooks (see image below).

This remarkable image taken from a P-38 by pilot Robert Symons during aircraft investigations of the "Sierra Wave" in 1950, shows a hydraulic jump and rotor cloud east of the Sierra Nevada Mountains facing south over the Owens Valley, CA, with winds blowing from west to east, i.e., right to left in the image:

Water vapor image, vertically propagating waves:

Animations can help sort out whether or not there are mountain waves--features are nearly stationary when mountain wave effects are occuring. These are vertically propagating waves (and also some gravity waves):

Vertically propagating waves often produce orographic cirrus on their downwind side. According to NOAA satellite expert Gary Ellrod, these waves are not turbulent when the clouds are next to the mountains. However, if they are downwind with a "Foehn gap" between the mountains and the clouds (due to strong subsidence in the lee of the mountains) then they are turbulent.

VIS image, vertically propagating waves with a Foehn gap:

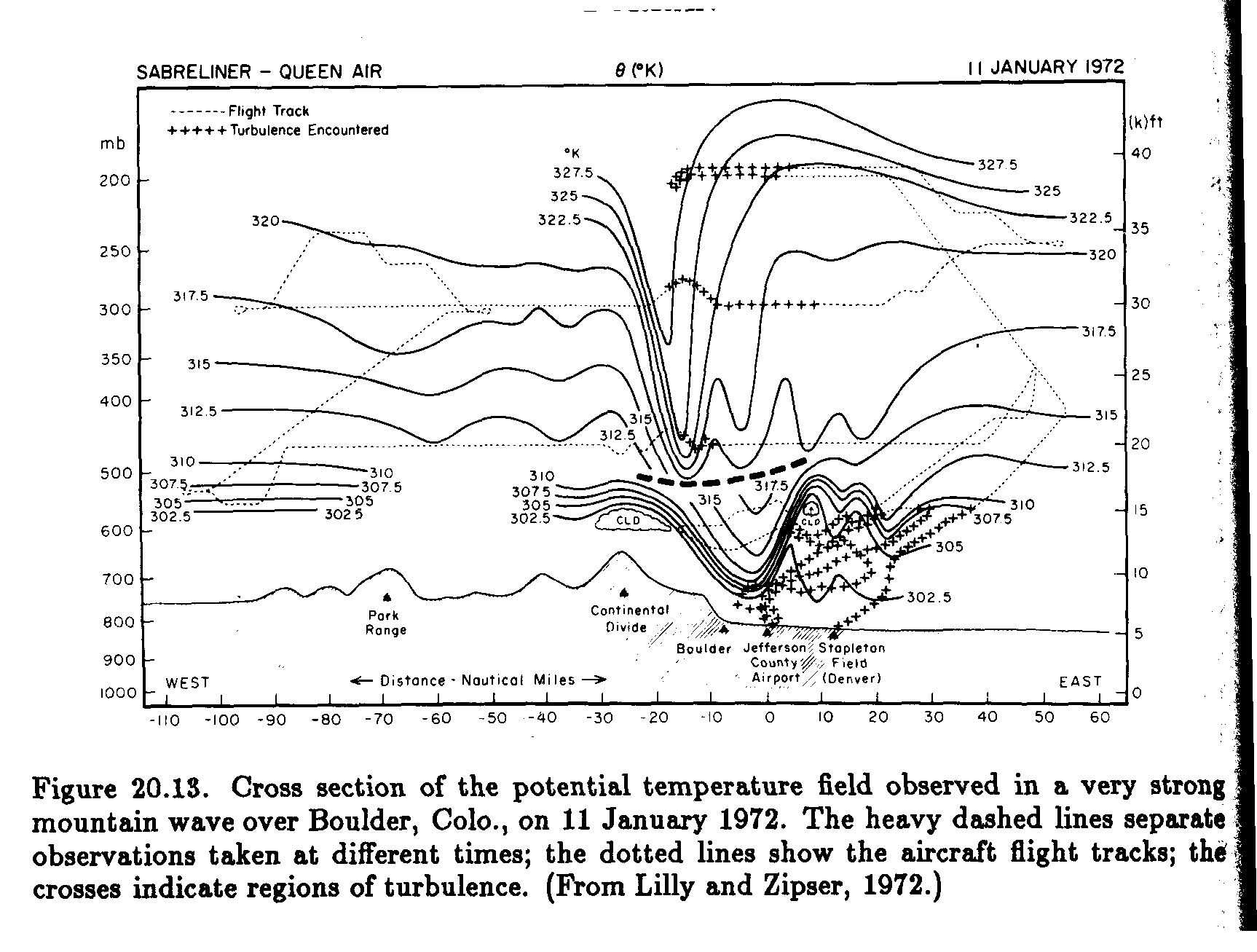

The following figure shows the path of an aircraft flight through a vertically propagating mountain wave and associated turbulence measurements:

A Case of Severe Turbulence Associated with Cloud Streets Developing Within a Mountain Wave Pattern

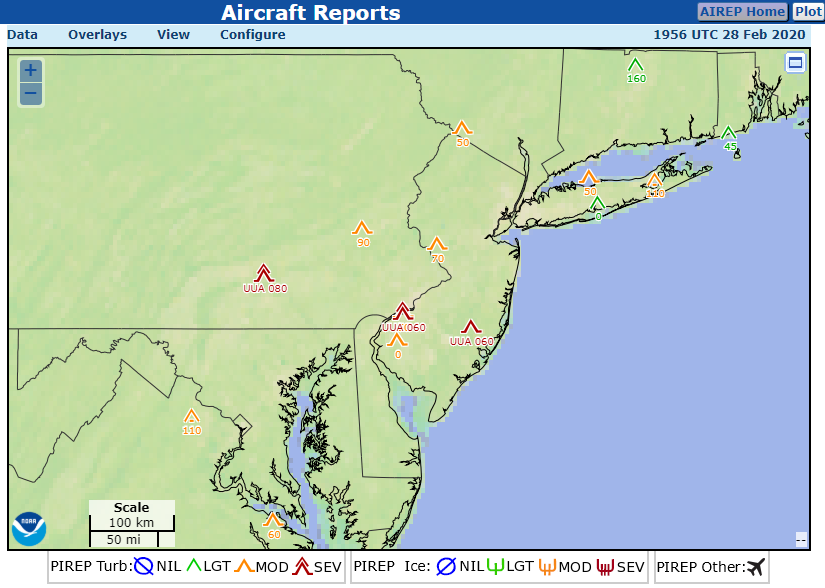

Text versions of PIREPs depicted above:

MDT UUA /OV LRP09005/TM 1945/FL080/TP C560/TB SEV 080/RM DURD

PHL UUA /OV 6NM E OF LNS/TM 1942/FL060/TP C550/TB SEVERE/RM PILOT REPORTS EXTREME TURB

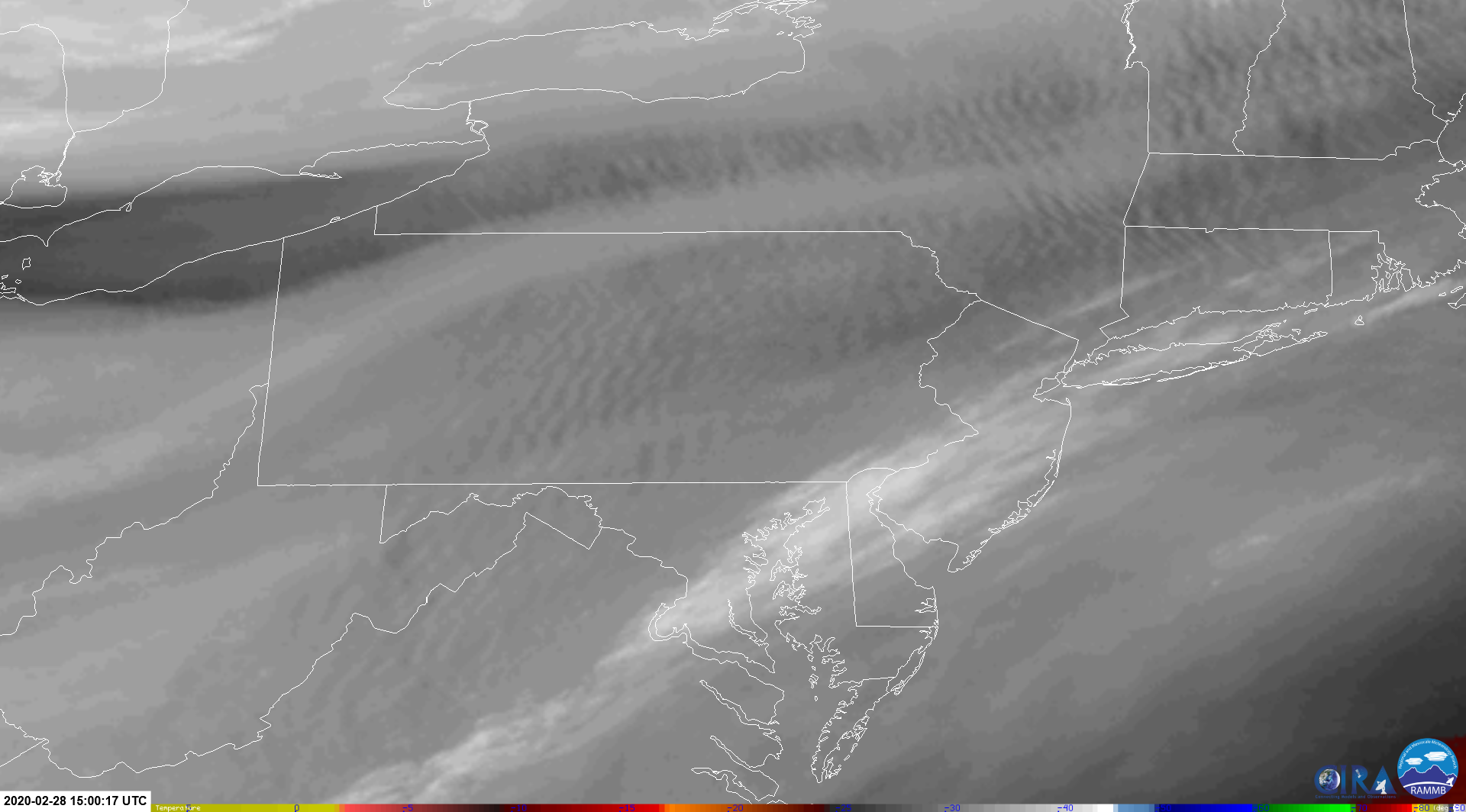

Visible image animation of cloud streets developing within a mountain wave pattern, producing severe turbulence.

Water vapor image animation of mountain waves with severe turbulence:

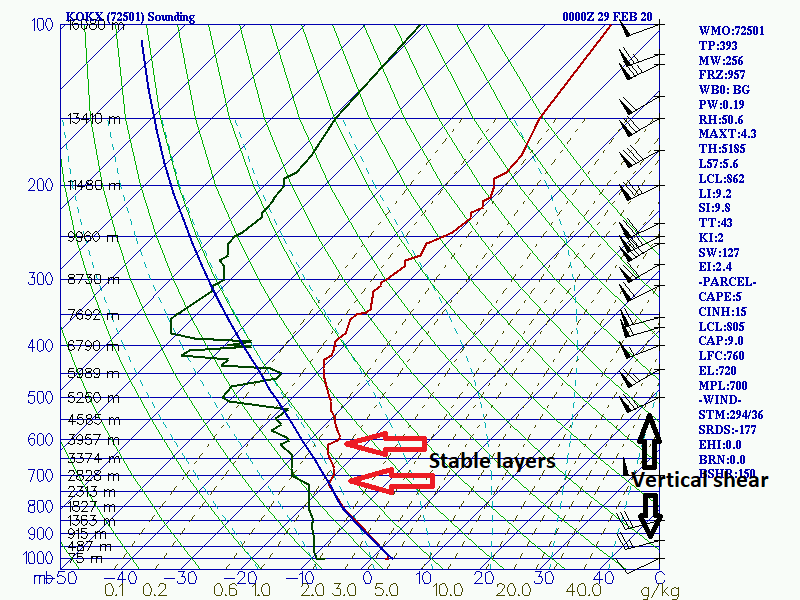

A sounding shows stable layers above mountain top level, and wind shear across the stable layers, with a neutrally stable boundary layer below: